Root Cause

Agentic Sufficiency Curve

Nov 22nd, 2025

Chris Rohlf

Since 2022, the USG has restricted access to advanced AI GPUs through successive rounds of export controls, all aimed

at limiting adversary access to large scale compute. While the specific parameters of those export controls and associated

policies continue to be modified there is still general consensus around the goal of preventing access to significant

quantities of high end AI compute by adversaries.

This strategy assumes the decisive variable in AI competition relies on access to the most capable GPUs in mass quantities.

There is good reason to support this logic given the value of AI in high stakes domains like intelligence and warfare.

But who wins the AI race won’t be decided by who can train the best models alone. There are many domains where a small

number of GPUs used for inference of the latest open weight models are capable of producing incredibly valuable outputs.

This is obvious to anyone who has run an open weight model, or written an agent to autonomously perform a task. While the

cost of inference is coming down on a per-chip basis, the number of AI workloads is growing and along with

it the volume of tokens and so costs overall are rising. The realities and constraints of those spiraling costs means

there is incentive to minimize GPU compute and to exploit the capability overhang in existing models to drive

agentic workloads that primarily run on CPUs at significantly lower costs. This is especially true for rote and well

understood tasks involving legacy technologies with minimal degrees of existing automation.

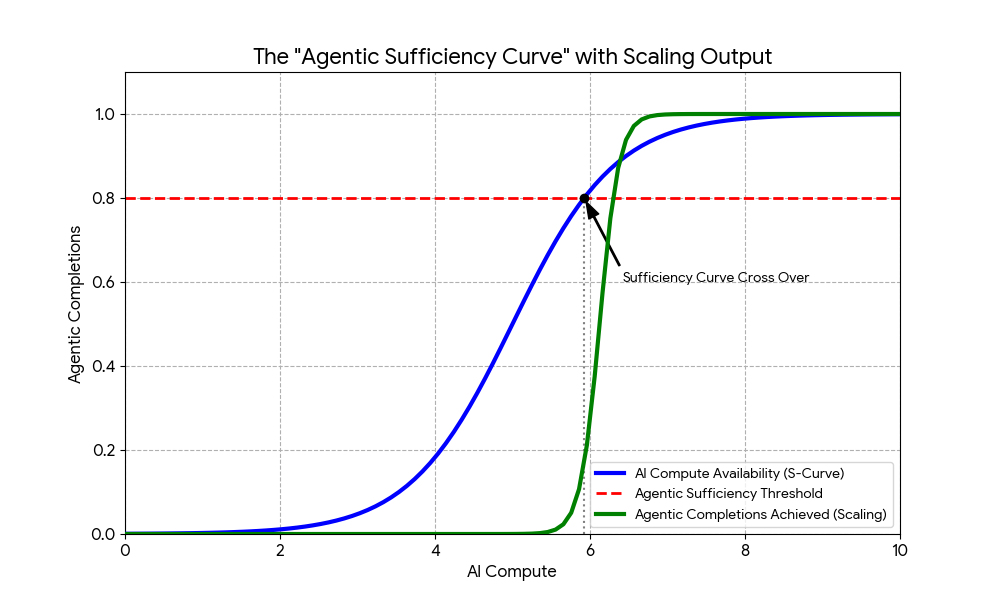

In this piece I introduce the ‘Agentic Sufficiency Curve’, a threshold where GPU capacity becomes good enough for a

specific problem domain through accurate initial inference and agentic throughput begins scaling on CPUs, memory, and I/O.

States don't necessarily need infinite frontier silicon to win the AI race, they need sufficient inference capacity and

vast amounts of cheap CPU that agents can leverage. In other words, once the blue line intersects with the red line, agentic

completions take off and the bottleneck shifts from GPU TFLOPs to commodity CPU cycles, memory bandwidth, and I/O.

The ‘Agentic Sufficiency Curve’ is just an attempt to formalize something that is likely very obvious to anyone who

has written an agent. The agent itself is a probabilistic program that is partially produced by inference on GPU but that

executes on low cost CPU.

There is also good reason to believe the cost of frontier model inference will continue to fall. Model architectures

improvements such as batching, quantization, speculative decoding, MoE architectures, and others have all pushed the

sufficiency point left. This means older GPUs can still clear the bar for inference that meets the threshold

and deliver the tokens per-second needed to drive and scale agent deployments. It should be noted however, that with

the emergence of test time compute and reasoning models, that large amounts of High Bandwidth

Memory (HBM) found on GPUs will continue to be important. Even with CPU driven agentic workloads, more GPU HBM will

always result in better throughput as it can transfer higher amounts of data across the token boundary to the CPU.

Semiconductor export controls aim to protect access to the latest silicon but not the area under the curve. Still, GPU

compute will remain more expensive than CPU for the foreseeable future and this means it is in the best interest of

companies and governments to shift as much of these workloads to agents (which execute on CPUs) after the sufficiency

threshold is met. Accurate inference is still critical because the model’s first few trajectories determine the entire

direction of the agentic workflow. A strong initial inference minimizes wasted CPU cycles, and prevents the agent from

wandering into dead ends that require expensive replanning steps. Every low accuracy agent trajectory forces a return

to GPU bound inference, so precision up front compounds efficiency across the whole agentic loop.

As an example, agent workloads in software vulnerability discovery and mitigation largely center around using LLMs to

drive traditional tooling such as fuzzers and static analysis tools. These combine short durations of token generation

with long tails of planning, retrieval, tool use, and verification. In these workloads, GPUs idle while agents wait on

network and system calls, overall throughput and agent output improves from smarter process scheduling, concurrency, and fewer

cache misses than from total GPU TFLOPs alone. This won’t be true of all problem domains, and as models get better and more

accurate we may reach a point where a small number of tensor operations performed in milliseconds results in the same

outcome and cost as hundreds of millions of CPU instructions over a longer period of time.

It’s all but guaranteed that frontier AI silicon will remain strategically important, but once an organization amasses

enough inference capacity to solve for a specific problem domain, the winning condition shifts to agentic saturation

driven by cheap CPU. If policy makers fixate only on who amasses the newest chips, they will miss the agentic crossover

and the point where a domain specific advantage comes from agent deployment, not amassed TFLOPs intended for training runs.